You’ve been told that the problem with climate change is that it’s expensive to fix.

Strangely, though, I’ve now worked in two markets where reducing emissions is profitable. Climate action has a positive net present value. It will save you or your company money. Even better, these are huge markets where we could get a lot of climate benefit. Yet still people aren’t doing them.

The first is building energy efficiency. Buildings contribute to almost half of the emissions here in the U.S. by using mostly electricity for lighting, heating, and air conditioning (EPA.) You’re probably sitting in a building right now that could significantly reduce its energy use and save money doing it, because reducing emissions in buildings is not difficult. Upgrading to LED lighting will usually pay for itself in less than a year. Upgrading thermostats or systems for controlling heat and air conditioning has about a two year payback. Even big projects like changing the windows will pay you back in seven to ten years.

So how many buildings do you see getting energy efficiency upgrades? Not many.

The second is methane from oil and gas production. Each year, 260 billion cubic meters of methane, what you and I call “natural gas,” is flared (burnt) at oil wells and natural gas fields or leaking from the ground there. This is 1.7 times the amount of natural gas Europe imports from Russia. (FlareIntel) It has the climate impact of 1.3 billion cars — almost all the cars in the world, or nearly seven times the emissions of all the world’s airlines. It’s also worth over $60 billion. Much of it could be profitably captured and sold.

Yet in many places where it happens, no one is rushing to either make the money or help the climate.

Say it — “That’s crazy!!!” But just saying it won’t solve the problem. First you have to understand why it’s like this. The answer is that you may have a mistaken understanding of what businesses actually do. You’ve been taught that businesses are there to “make money.” But it’s not true. Businesses want to make products and sell to customers. (If you don’t believe me, ask yourself this: When was the last time you sat in a business meeting about improving products or increasing sales? What about a meeting about net present value?) Thus, if a project doesn’t increase sales, it won’t be a priority or top of mind, even if it could make money and benefit the environment.

Every day at a building, people work to lease more space at higher rents. Every day at an oil and gas company, people work to produce and sell more fuel. They’ll spend gobs of money to make buildings look nicer for tenants or drill more oil wells, but they’re not thinking about all the side projects that have positive net present values or climate benefits. And they won’t, unless it helps them lease more space, increase rents, or sell more fuel. Conversely, if they could turn emissions reductions into benefits for their customers, so those customers could look good to regulators, investors, and the customers’ customers, then they’ll be more likely to do projects to reduce emissions.

That’s the missing link.

Easy to say, but very hard to do. How do you actually transfer emissions reductions between companies? Each company runs its own siloed accounting systems, so integration between any two companies is always costly. You might think regulators could step in and require companies to report their emissions and transfers between each other. Unfortunately, since supply chains span multiple industries and countries, no regulator could actually do this. Finally, big tech vendors could (and would like to) do it, but most companies wouldn’t want that.

This is a job for blockchain.

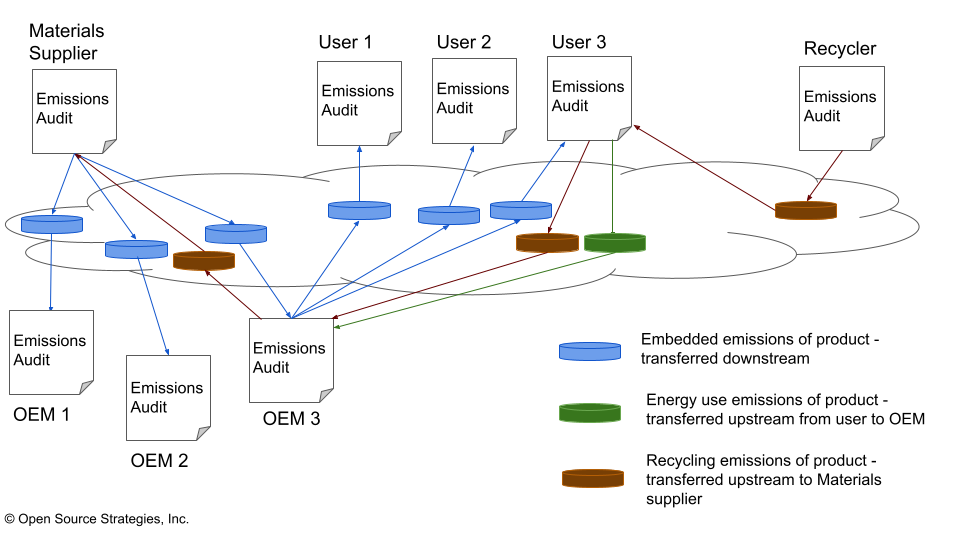

Blockchain enables collaboration without a centralized authority. A token on the blockchain is minimalist in design, carrying just enough information for a transaction, yet trusted by all parties because it’s stored immutably on the chain. Data and identities are encrypted and could be kept private and shared as needed. A blockchain could thus connect all the parties in a supply chain, no matter how spread out it is. Each party could use tokens to transfer the embedded emissions of its products and services both downstream to its customers and upstream back to its suppliers. The recipient could then use the tokens in its own emissions audit, then calculate its embedded emissions and pass them along:

For more details on the mechanics and how it fits with existing emissions accounting standards such as the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, see the white paper “Blockchain Mechanism for Tracking GHG Emissions through Supply Chain.”

Building energy efficiency and oil and gas methane emissions are just two markets I’ve become familiar with. I’m sure there are many more places where we could emissions at low costs, yet we’re not doing them enough. Overcoming such inertia is what we’re working on in the Supply Chain Decarbonization Project at the Hyperledger Climate SIG. Please sign up below or at this page to get updates about our progress.